You have a code base that you re-use and upload as distinct apps in the App Store. They are separate apps because each targets a different market.

It was great, you can target each customer group through the corresponding app’s icon, imagery, and app store metadata. Customers finds it easy to locate the app that they need, to download what they care about, and not waste bandwidth for content they don’t use. You can leverage work on that single code base multiple times for each app. Things were good.

These apps may be city guide apps, vehicle driving exam simulation apps, or math games for different age groups. A city may have its own corresponding city guide app. Motorcycles, sedans, and, lorries each get its own driving exam simulation app. Toddlers, pre-school, and school-age children would be targeted with their respective math game app. Nevertheless apps in each of these categories were built from their respective common code bases.

One day as you were updating one of these apps, Apple’s app review rejected the update and stamps you to be a spammer by means of Guideline 4.3:

… Developers “spamming” the App Store with many versions of similar Apps will be removed from the iOS Developer Program….

We noticed that your app provides the same feature set as other apps you’ve submitted to the App Store; it simply varies in content or language….

Apps that use the same – or very similar – icons make it difficult for users to find apps and are considered a form of spam….

Please combine apps with a common features set into a single “container” app that uses the In-App Purchase API to deliver different content.

“Move into a container app? How can we do that? We have existing users who bought our apps and they won’t like it if we invalidate their purchases. Amalgamating current apps into a new container app would result in a big big and bloated app — large portions of content won’t be relevant for any particular group of users. How can we target different markets through one app?” You might exclaim.

Relax. There are solutions to those problems.

Read on and follow the recommendations in this article to migrate your different-yet-similar apps into a single container app and continue to make money on the App Store. Implementing these suggestions involves non-trivial work, but at this point there’s not much other options.

In short, these are what you need to do to move into a single “container” app:

- Migrate individual apps’ licenses into in-app purchases in the new container app.

- Use on-demand resources to manage content for the different target markets.

- Deep link into your apps from online advertisements instead of linking to the App Store.

Migrating App Licenses

The first order of business when Apple mandate you to migrate into a container app model is to ask for leniency. Tell the reviewers that you would migrate into a container app but you need to push updates so that you can migrate existing users’ licenses into the new app. Apple would likely give you two months of grace period and allow the update to go through. In exchange you need to start preparing both the current apps and create the new “container” replacement app which would replace them.

There are three concerns you would need to address to migrate existing users’ licenses:

- All the “old” apps would need to message the new container app of the user having license to it.

- The new container app would need to receive these messages with confidence of their authenticity and activate the corresponding feature(s).

- Once migrated, users should no longer need to install any of the old apps to activate features in the new container app.

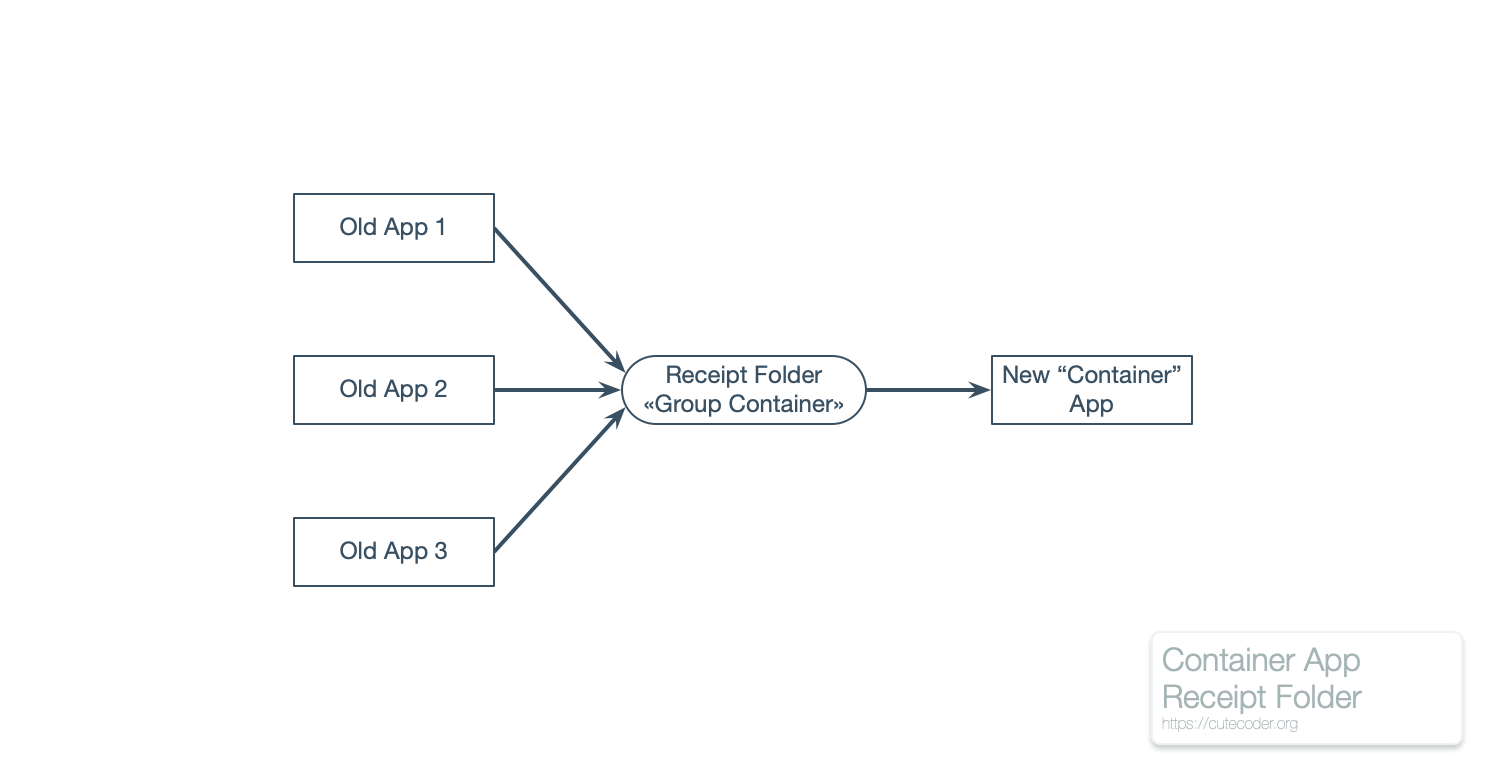

Those first two concerns can be addressed by having the old apps copy its respective receipt file into a group container. This is a shared folder inside the user’s device that you create and designate to hold receipt files. In turn, the new app would read all the files there and use standard receipt validation methods to verify their legitimacy.

Those old apps can use a certain naming convention to prevent different apps from overwriting each other’s receipt files. Naming these receipt files after their respective apps’ primary bundle identifier would be a good idea.

This group container isn’t normally shown by the iOS Files application, hence should unlikely be tampered. However there are 3rd party applications that can show (or modify) these files when the device is connected to a host computer. Therefore don’t skimp on validating these receipt files.

Migration would be complete when the user no longer need the old app to activate functionalities in the new app. The user may move to a different iOS device. There may be a new operating system update causing the app to stop functioning and thus can’t run to enable features in the new app. Remember that you would likely be barred from updating those old apps after the grace period has lapsed.

Therefore you would need to migrate the user’s license from the old app by creating an equivalent license in the new app. That way when the user reinstalls the new app, they won’t need the old app any longer to access features originally provided by the old app.

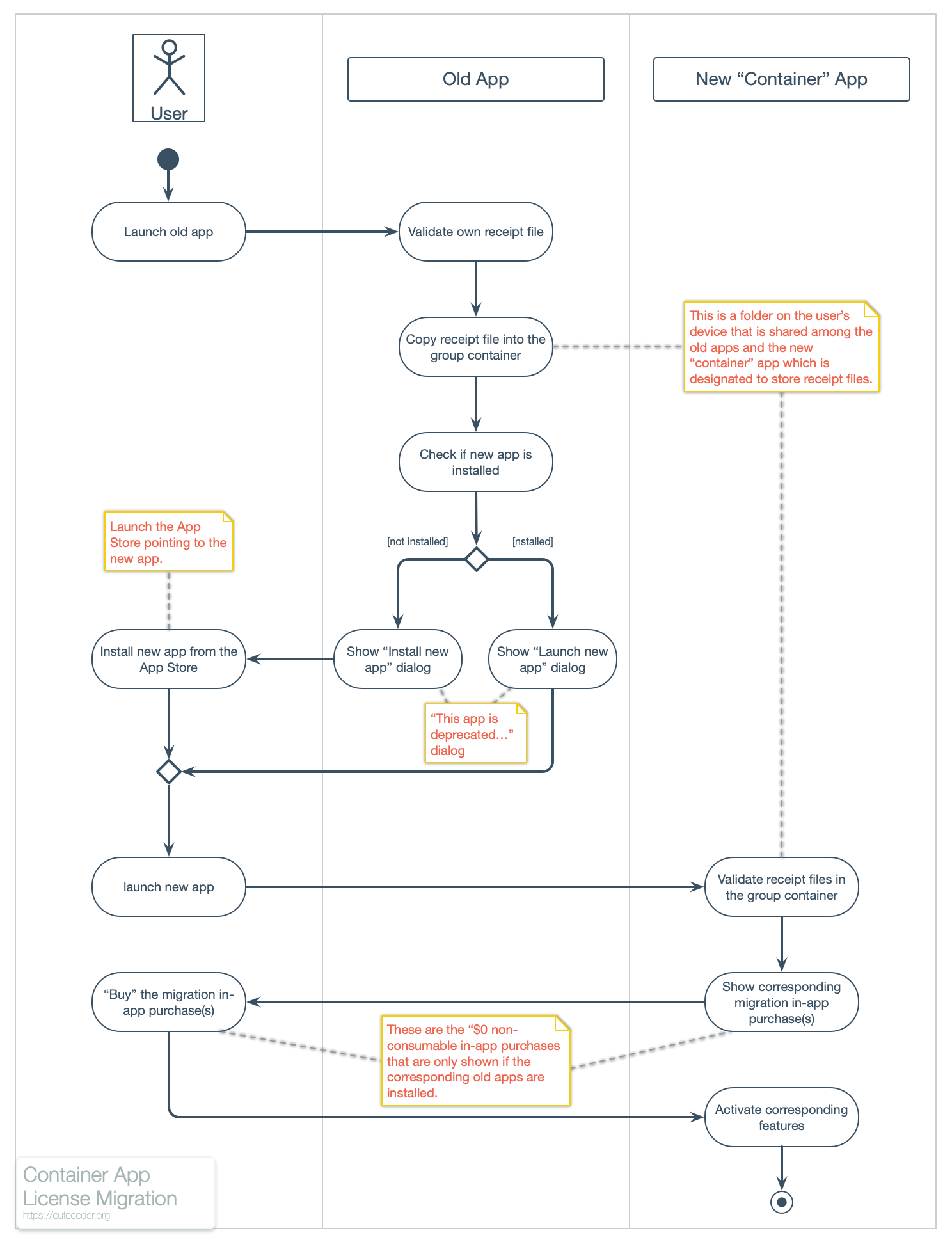

A good way to migrate licenses is via in-app purchases. For every “old app” create a $0 non-consumable in-app purchase (iAP) in the new app. These “grandfathering” iAPs would only be visible when the new app has validated the corresponding license coming from the old app. Having purchased the iAP, the user would only need to “restore purchases” to get the functionality back when reinstalling the app or moving to a new device.

In contrast, the new app won’t make those special iAP accessible to the user without a valid receipt file from the old app. New users would need to buy the properly-priced iAP instead to unlock the functionality. This means that for every functionality to be unlocked there would be a pair of non-consumable iAPs:

- The $0 “grandfathering iAP” for existing users.

- The non-zero price iAP for new users.

Then it is a matter of directing users from the old app to “buy” the corresponding $0 iAP in the new app. This flow could look like the following:

When the user launches the old app, it would validate its own receipt file as per normal and then copy it into the group container. The old app would then check whether the new app is installed (one way is by checking canOpenURL(_:) of a custom URL scheme handled by the new app. It then show a “this app is deprecated” dialog with an option to either install the new replacement app or launch it. Upon launching the new “container” app, it would validate the receipt file(s) in the group container. For each valid receipt file, it would show the corresponding “grandfathering” iAP(s) and prompt the user to “purchase” them.

On a side note, it looks like iAP would be enabled for family sharing in iOS 14 / macOS 11. If your “old apps” are paid apps with family sharing enabled, then the same purchases should be share-able in the new app when the new operating systems are available.

This is about migrating a purchased app into a non-consumable iAP belonging to another app. The technique should work similarly to migrate non-consumable iAPs between apps. But migrating subscriptions should be easier since they can be shared across apps.

On-Demand Resources

When combining the functionalities from the old apps into the new container app, you should port the corresponding static data of the old app as on-demand resources (ODR) in the new app. These include (but not limited to) images, videos, custom data files, or even button glyphs.

ODR are data files (and asset catalog entries) that are uploaded by the developer as part of the app bundle. However they are downloaded to the user’s device on-demand. The App Store hosts these files similar to the way it hosts your app. But your app has full control when these files gets downloaded into the user’s device.

The application requests certain ODR via its associated tag. When a tag is requested, all ODR having that tag are downloaded. These files would remain on the user’s device as long as you need them to be. There are APIs to manage the lifecycle of these ODR (again via its tags) and to monitor its download progress.

When the user makes an in-app purchase, it is a good opportunity for the app to start downloading the ODR associated with it. You can provide functionalities for the user what content that he wants to keep off-line — similar to how the Apple Music app provides options for both offline content and on-demand streaming.

Deep Linking

Having a “container” app would likely change your Internet marketing strategy. Instead of creating web advertisements that links to the App Store (the way it was done for the “old app”), they would need to permanently link to dedicated pages in your own website.

In turn, these landing pages would provide details on that specific content in your app. Be it about a guide of a particular city, an exam for a certain vehicle type, or a math exercise for a particular age group. The page would then contain a mobile deep link to the app’s content or a link to the “container app” in the App Store.

Then you tie the landing page with the app’s content using universal links. These would prompt the user to open the corresponding content inside the app (when it is installed) or install the app from the app store.

Having universal link, a mobile deep link, and an App Store link is important because you can’t control how the user open your web page. Universal links would show up on iOS’ built-in Safari browser, but not other browsers. The mobile deep link would work on an iOS browser when the app is installed, but not otherwise. The App Store link is the last resort since it works both on the device and on another browser (even in Windows), but linking to the “container app” risks confusing the user.

But at least having a dedicated landing page means you can better measure the click-through rate of each advertisement. That means more fine-grained measurement of the return-on-investment of each copy and channel permutation. This is something that you couldn’t do before if you linked directly to the App Store from your advertisement copy.

Next Steps

If you haven’t been rejected by “Guideline 4.3 – Spam” it may be a good idea to start having a shared receipt file folder. That would help you should you need to migrate an app’s license or provide upgrade or cross-grade discounts. Having dedicated permanent landing pages for your app’s contents would be good idea and should help your SEO efforts.

But if your recent update was recently rejected by Guideline 4.3 and you are instructed to migrate into a container app, then this article is your rough migration plan. Take a deep breath then have a discussion with your iOS developers, web developers, and marketing people to come up with a concrete task list with due dates for the migration.

PS: if your different-but-similar apps is developed for differing entities (e.g. the white label business model), you might want to consider transferring it out of your Apple Developer Program account into your clients’ own accounts.

0 thoughts on “How to Combine Apps into a Single Container App”